Ghalib’s Most Famous and Popular Shers Translated and Discussed

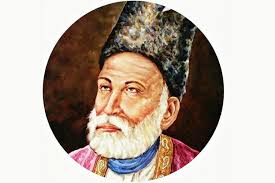

Maharaj Kaul translates and discusses Mirza Ghalib’s (1797 – 1869)

most popular and famous shers:

Ghalib Sher 24:

qafas meñ mujh se rūdād-e-chaman kahte na Dar hamdam

girī hai jis pe kal bijlī vo merā āshiyāñ kyuuñ ho

Translation:

in the cage, telling me the events of the garden, don’t be afraid, friend

the one on which lightning has fallen yesterday, why would that be my nest?

Discussion:

As it happens with some of Ghalib’s verses, several meanings can be alluded to this one. He was a master of compression: in the least number of words, he could construct a meaning that could be interpreted differently by different readers. My interpretation of this verse is that a bird in a garden was captured by a gardener and put in a cage in the garden, from where he could see the garden. A new bird is captured by the gardener and put in the same cage in which the earlier bird has been a prisoner. The new bird after he is put in the cage starts at once a conversation about the lightning that struck the garden a day earlier, destroying the earlier prisoner’s nest. But in midway of his conversation he stops, afraid that the news of the destruction of the earlier bird’s nest will pain him. But in spite of the halted news of the new bird, the old bird realizes that the new bird wanted to tell him about the destruction of his nest, as he had either seen it himself yesterday, or by judging the new bird’s hesitation to give the bad news. The old bird has made peace with the destruction of his old nest, as he lives there no more. He has a new life in the cage, with which he wants to make peace. This is expressed by the old bird telling the new bird that the destruction of his old nest is irrelevant, as he leads a new existence living in the cage.

Below three verses of Ghalib are being grouped together, as they are

thematically connected. Because of this the verse numbering in this

posting had to be put in the descending order:

Ghalib Sher 21:

rahye ab aisī jagah chal kar jahāñ koʾī nah ho

ham-suḳhan koʾī nah ho aur ham-zabāñ koʾī nah ho

Translation:

one should go now and live in such a place where there would be no one

there would be no speech-sharer and there would be no language-sharer

Discussion:

Ghalib would like to move to such a place where there would be no companion, no one to talk with, and no one who would understand his language. It is because he has had with them, they have given him a lot of grief. He wants absolute isolation.

Ghalib Sher 22:

be-dar-o-dīvār sā ik ghar banāyā chāhiye

koʾī ham-sāyah nah ho aur pāsbāñ koʾī nah ho

Translation:

without-door-and-walls-ish house ought to be made

there would be no neighbor and there would be no gatekeeper

Discussion:

Ghalib would like to have a house made without doors and walls. Obviously, it implies that no neighbors exist. It is like living in a desert or an island without people. Obviously again no doorman would be needed in such an existence. All these requirements are needed by Ghalib because he has had enough grief with people.

Ghalib Sher 23:

paṛye gar bīmār to koʾī nah ho bīmār-dār

aur agar mar jāʾiye to nauḥah-ḳhvāñ koʾī nah ho

Translation:

if one would fall sick then there would be no sick-attendant

and if one would die then there would be no lament-reciter

Discussion:

Ghalib does not want any attendant to help him, if he got ill. Nor would he want any lament-reciter to lament his death, as was required by the prevalent culture. It is all because he is so sick and tired of human society. He has had enough of it.

General Discussion on The Above Three Verses:

The above three verses are considered among the worst of Ghalib’s poetry. Such negativity, such emotionalism. He wants to live in an unpopulated place, where he won’t see even the face of a human being, as he has been deeply hurt by them. Such a childish emotion.

In 1862 Ghalib is supposed to have written to some Ala’i:

I envy the situation of island-dwellers in general, and of the lord of Farrukhabad in particular, whom they put off the ship and left on the shore of the land of Arabia. Hah! [ahāhāhā]: {127,3}. (Arshi 246)

What he is expressing is that he would like to live on an island, cut-off from the commotion of the world. But in the above three verses he has gone even beyond that in wanting to live without human beings around him.

These three verses are independent of each other, but thematically they are similar, so they are like a ghazal.

Their popularity also stems from Suraiya’s singing of them.

Ghalib Sher 20:

go hāth ko junbish nahīñ āñkhoñ meñ to dam hai

rahne do abhī sāġhar-o-mīnā mire āge

Translation:

although there is no movement in the hand but eyes have power

let the wine glass and flagon remain before me

Discussion:

Due to old age or dissipation of passion the body feels weak, but

still the eyes have power. It is not all over yet. So, let the wine glass

and the flagon (a large container of wine, which has a handle and

a spout) stay on. Man’s life is dependent on the vigor of body, but

beyond that the mind still exerts power over his existence.

Ghalib Sher 19:

bāzīchah-e at̤fāl hai dunyā mire āge

hotā hai shab-o-roz tamāshā mire āge

Translation:

a game of children the world is before me

happens night and day a spectacle in front of me

Discussion:

Ghalib sees the world as games that children play. The spectacle goes on day and night. He does not think much of it, he is unaffected by it. This means that he has an inner life that he lives for and by it. His division of his internal and the external lives is strong. This is clearly different from run of the world people.

Ghalib Sher 18:

ham ne mānā kih taġhāful nah karoge lekin

ḳhāk ho jāʾeñge ham tum ko ḳhabar hote tak

Translation:

I concede that you won’t show negligence but

dust I will become by the time the news reaches you

Discussion:

The lover has come to concede that his beloved will not be negligent in taking care of him when he is in some dire condition, but the problem is that she may have gone so far away or is in some difficult situation such that his bad news may not reach her in time. So, this is the dark cloud hanging over the lover’s head.

Ghalib Sher 17:

ham ko un se vafā kī hai ummīd

jo nahīñ jānte vafā kyā hai

Translation:

we have hope for faithfulness from the one

who doesn’t know what faithfulness is

Discussion:

Ghalib says that the irony is that we are expecting faithfulness from a beloved who does not know what faithfulness means. It could be that she is so young yet to know what it is, or that she is old enough to know what it is, but does not think it is required of her. That is faithfulness is not a requisite in love. On one hand the lover is going in the full fever of love with all its trappings, but on the other hand the beloved does not seem to care for faithfulness.

Ghalib Sher 16:

ishq mujh ko nahīñ vaḥshat hī sahī

merī vaḥshat tirī shuhrat hī sahī

Translation:

love it may not be let it be madness

my madness your fame let it be

Discussion:

Ghalib tells his beloved that let it be his madness as she feels his love is. But his madness has imparted a fame of specialness on her. In other words, even though she thinks his passion for her is madness, but nevertheless it has cast her as a special person in society.

Ghalib Sher 15:

yih nah thī hamārī qismat kih viṣāl-e yār hotā

agar aur jīte rahte yihī intiz̤ār hotā

Translation:

this was not our destiny that union with the beloved would take place

if we had kept on living there would have been the same waiting

Discussion:

Ghalib laments that it has not been his luck to have had a union with his beloved. Also, he has come to the realization that had he and his beloved waited longer, the union between them would still not materialize. This is so because it is their destiny.

Ghalib Sher 14:

ishq se t̤abīʿat ne zīst kā mazā pāyā

dard kī davā pāʾī dard-e be-davā pāyā

Translation:

through passion the being found the relish of life

found cure for a pain found an incurable pain

Discussion:

Ghalib says that by means of passion a human being can make life enjoyable, but that passion is not easy to cultivate and hold on to, because of the problems associated with it. So, while the enjoyment in life is cultivatable, but the fuel to support it is problematic.

Ghalib Sher 13:

muḥabbat meñ nahīñ hai farq jīne aur marne kā

usī ko dekh kar jīte haiñ jis kāfir pah dam nikle

Translation:

in love there is no difference between living and dying

seeing her we live the infidel who would make us die

Discussion:

Ghalib says that in love one lives as well as dies, as it is a challenging experience that involves a relationship with another person. Depending on her state of mind one’s feelings can swing from living to dying.

Ghalib Sher 12:

baskih dushvār hai har kām kā āsāñ honā

dmī ko bhī muyassar nahīñ insāñ honā

Translation:

it is difficult for every task to be easy

even for man it is not easy to be human

Discussion:

It is difficult for every human task to be easy. For man also to be human is not easy. Man is the physical aspect of the human race, being human is his qualities of love, sacrifice, compassion, etc.

Ghalib Sher 11:

nah thā kuchh to ḳhudā thā kuchh nah hotā to ḳhudā hotā

ḍuboyā mujh ko hone ne nah hotā maiñ to kyā hotā

Translation:

when there was nothing there was God if nothing happened God would be created

I was drowned by my existence if I didn’t exist what would happen

Discussion:

It is a deeply philosophical sher by Ghalib. He says that when there was nothing in the universe, there still existed God; and if nothing was going on in the universe, the phenomenon of God would still be occurring. Ghalib says that his existence has ruined him. Because if he had not existed, he would be a part of God, a superior situation than his human situation.

Ghalib Sher 10:

hazāroñ ḳhvāhisheñ aisī kih har ḳhvāhish pah dam nikle

bahut nikle mire armān lekin phir bhī kam nikle

Translation:

all the thousands of longings are such that over every longing I would die

many of my wishes were fulfilled but still few were fulfilled

Discussion:

Ghalib says there are thousands of desires in life such that, for each of them one would sacrifice his life. Many of his desires were fulfilled, but still they turned out to be few.

Ghalib Sher 9:

koʾī vīrānī-sī vīrānī hai

dasht ko dekh ke ghar yād āyā

Translation:

it is a desolation like desolation

seeing the desert home came to mind

Discussion:

This is a famous sher known for its vast ambiguity. Is Ghalib reminded of his home seeing the desolation of the desert? Or is he longing to be at his home, seeing the desolation of the desert? Or, is he in a state of the mood of desolation; then, seeing the desert he is reminded of his home, as a state of relief. We cannot understand what Ghalib had in his mind writing this couplet.

Ghalib Sher 8:

koʾī mere dil se pūchhe tire tīr-e nīm-kash ko

yih ḳhalish kahāñ se hotī jo jigar ke pār hotā

Translation:

let someone ask my heart about your half-drawn arrow

where would this romantic pain have been if it had gone through beyond the liver

Discussion:

The half-drawn arrow thrown by Ghalib’s beloved at him, whether by amateurishness or by design, has produced a beautiful pain in him. On the other hand, had it been thrown fully by her, he would have been dead, but without any pain. This pain is what produces the feeling of love. So, he is better off in pain than being dead.

Ghalib Sher 7:

ġham-e hastī kā asad kis se ho juz marg ʿilāj

shamʿa har rang meñ jaltī hai saḥar hote tak

Translation:

for the grief of life Asad what would be the cure except death

the candle in every color burns until the coming of dawn

Discussion:

Ghalib asks what is the cure of the unavoidable grief of life. He answers his question by saying it is death. He laments further that life is like a candle, which keeps on burning all night till dawn. Then when its wax runs out it extinguishes. When the flame of life is burning it can encompass everything imaginable. This is the inherent tragedy of human life. The second line of the sher is awesome, as it tells that while alive a man can be an element in all the possibilities. That is, the scope of human life is great; man’s consciousness can take him anywhere.

Notes:

Asad is the middle name of Ghalib. His full name was Assad Ullah Khan Ghalib.

Ghalib Sher 6:

āh ko chāhiye ik ʿumr aṡar hote tak

kaun jītā hai tirī zulf ke sar hote tak

Translation:

a sigh needs a lifetime until the appearance of an effect

who lives until the subduing of your curls

Discussion:

It is among the most famous as well as popular shers of Ghalib. Most of its translations into English have been marred by the translation of the second line of the sher. They have been given to the effect: ” who will live until she deigns to pay attention to her lover.” The word “sar” means subduing or disentangling or softening. So, “zulf ke sar hote tak” means ” until the hair curls are disentangled, subdued, or softened.”

Ghalib says that his sighs for his beloved will need a lifetime to be effective, as it is the nature of human life. But while he is waiting miserably, his beloved does not pay any attention to him, as she is busy disentangling the curls of her hair. This is the utterly painful contrast between the two.

Ghalib Sher 5:

ham ko ma.alūm hai jannat kī haqīqat lekin

dil ke ḳhush rakhne ko ‘ġhālib’ ye ḳhayāl achchhā hai

Translation:

we know the reality of paradise but

to keep the heart happy Ghalib this idea is good

Discussion:

This is one of Ghalib’s famous shers. It says that we know what paradise is actually, an illusion; but to keep oneself happy and distracted this idea is good.

Ghalib Sher 4:

merī qismat meñ ġham gar itnā thā

dil bhī yā-rab ka.ī diye hote

Translation:

in my fate if so much sorrow was ordained

hearts Oh God many should I have been given

Ghalib Sher 3:

dil hī to hai na sañg-o-ḳhisht dard se bhar na aa.e kyuuñ

ro.eñge ham hazār baar koī hameñ satā.e kyuuñ

Translation:

it’s just a heart no stony shard why shouldn’t it fill with pain

I will cry a thousand times why should someone complain

Ghalib Sher 2:

ishq par zor nahīñ hai ye vo ātish ‘ġhālib’

ki lagā.e na lage aur bujhā.e na bane

Translation:

love we do not have power over it is that flame Ghalib

it may not ignite when we ignite it nor it may extinguish when we try

Ghalib Sher 1:

ishrat-e-qatra hai dariyā meñ fanā ho jaanā

dard kā had se guzarnā hai davā ho jaanā

Translation:

the desire of a drop is to obliterate itself in a river

pain growing beyond limit becomes its own cure

Discussion:

Ghalib says that the ecstasy of a drop of water is to lose its little identity by merging with the much larger expanse of a river, thereby enriching its existence vastly. Let us say there is a man who lives in a small village, where he leads an ordinary life. Then he decides to migrate to a large metropolis as he feels he is not living fully. Though by moving to the metropolis he loses his identity but he vastly gains in the scope of his profession and culture. It is this expansion of mind what Ghalib is referring to.

The second line says that when a human being suffers very much due to something, the suffering elevates his fortitude to tolerate it. Great suffering challenges the human spirit, giving birth to a high threshold of forbearance in him.

Suffern, N.Y., April, 2024

www.kaulcorner.com

maharaj.kaul@yahoo.com

test