1.Excerpt from my book, Inclinations and Reality (2010)

My uncle Papaji was just three years younger than my father. He was born shy, aloof, and brainy. He had few friends in his younger years. It was only in his later years that his efforts to come out of his cocoon paid off and he became more sociable and assertive. But sometimes in his overzealousness he would become an uninhibited and an opinionated talker, making extreme statements on people and things. He excelled as a student and used deft strategies to score high in exams. After completing his education in Kashmir, he went to Government College in Lahore, which was considered the Oxford University of India at that time, to get a Master’s degree in English. Given his emotional personality, it was strange that he chose to take up literature instead of physics, history, or political science. On returning to Kashmir he briefly taught English, but having qualified in Kashmir Civil Service he became a police officer. Again, a police officer’s job was not in synch with his personality but he took it because it was monetarily a more rewarding job than other viable jobs, with potential for better growth than an English professor’s job.

He married into a family not socially as prominent as Kauls were. He did so because he valued the education of the woman in question, who was called Pyari in our family after her marriage. There was another reason for marrying in that family; it allowed his and his wife’s wedding gifts to be transferred to his younger sister, Gorajigri, when she would get married two months later. Pyari was a double college graduate, a regular graduate and a teaching graduate. She was also the first teaching graduate in the state. These qualifications gave her a special status in Kashmir those days. The irony is that her education brought a lot of problems in her married life, as she refused to move with Papaji from Srinagar many times whenever he was transferred to different districts of the state on the grounds of not willing to abandon her duties as the headmistress of a girl’s school. Also, she did not share his intellectual tastes and found him cold and unromantic, describing his personality as lacking in passion.

For about the next three decades and a half in the police service, my uncle blazed a trail of devotion to duty, incorruptibility, and efficiency. He became one of the most iconic figures in the state. Being highly principled, stern, and unbending, he was feared at his work, both by his subordinates and his superiors. Together with his superior professional abilities, he became bête noire of the higher state management, as they did not know what to do with him. He was among a few non-bribe taking police officers in the state, which made his superiors uncomfortable; his intellectual stature and high-mindedness made them nervous. He could not be fired, so he was often transferred to different districts of the state. He became a shining symbol of honesty and “efficiency” (a word used for professional abilities in India, which seems to have come from the old British management mindset) in an ocean of public corruption and stained morality. Add to this persona his six-feet height and reed-like leanness, he became a visible image of strength and sharpness.

After being treated as a pariah almost all his career, the crowning glory came almost at its end when he was promoted as the head of the police for the state (called IGP, Inspector General of Police, in those days). How did this happen? Customarily, Kashmir IGPs were recruited from outside the state. As the current IGP’s tenure was coming to an end, Papaji went to the state chief minister, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, asking him if local police officers lacked the ability to become an IGP. Abdullah, known for his pride in Kashmiris, responded that that was not the case and that future IGPs could be sourced internally. Lo and behold, in the next recruitment process, Papaji was selected for the post. This big feather on his professional cap apparently mitigated the years of step-motherly treatment he went through in the police organization.

With all the successes in his career, family, and social life, he remained less than happy. In my 25 years of correspondence with him, he complained many times about his inability to see much value in life; turning him almost into a nihilist. He often saw life as a cruel joke played by gods on the innocent and helpless human beings. He would quote Shakespeare from King Lear, “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods: they kill us for their sport.” He unconsciously believed that intelligence was an end by itself; nothing more was needed to live. That is, no faith in a system of thought was required to live, like in religion, art, science, etc. All that was needed was good brain power and the knowledge of the hard realities of life. The supreme irony of his life was that while he had evolved to achievements in character, intellect, and cerebral pyrotechnics, he had missed the spiritual dimension of human life. His perennial disenchantment with life provoked Babuji, his elder brother, to coin an epithet for him, “A Devdas without a Paro.” (Devdas is the legendary hero of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s novel of the same name. Devdas leads a very sad life and hastens its end by alcoholism, because he is unable to marry his childhood sweetheart, Parvati)

During his police career and later when he retired, he took refuge in books. He read widely in English. He loved Urdu poetry and could quote many a verse fluently. He was also good in quoting from English literature. He questioned some of the basic ways in which our society lived, thinking they were hypocritical and therefore of not good value. The problem was that he was much less emotional than the common people, so unable to understand some of the popular social intercourse. He believed all the prophets of mankind had failed it. He thought Kashmiri Pandit refugees did not deserve much sympathy as they were doing all right. Our correspondence was impregnated with arguments and debates as we were emotionally and intellectually antipodeans and, therefore, our views on art, culture, civilization, etc., were on the opposite ends. With Pyari’s untimely demise, and emigrating to New Delhi in 1990 due to the militancy in Kashmir, he struck the lonely phase of his life, which did not leave him till the end. Books did not provide permanent relief to him. He often asked me if book reading is all that life is about.

His influence on the family and the personalities of its members remains strong. Because of his high moral integrity, that too in a highly corrupt society, he has left a significant record of his services, a scintillating impression of his character. His life looks to be tragic to me because he had been born with the capabilities to do a lot more than he did—both in public and intellectual arenas. The following verse, written by me, may make my point clearer:

He came as a beacon penetrating the dark overcast skies,

To illuminate a patch below, to stir a cleansing

Of its stained fabric, to show us the new way to live.

But somewhere he lost interest in his work

And folded his supreme abilities and character,

To rue on unfairness of life, to lament on its immutable pain.

But I realize all of us are born one-piece. That is, our limitations are a part of our total personality. Papaji, on a larger canvas of his life, could not have been any different than he was. This is the uniqueness of every person, laced as it is with human dimension.

It is both ironic and unfortunate that most of the third-generation youngsters in our family did not know his achievements and his character, leaving them bereft of the inspiration he imbued in others. For me, during my exile years, he offered me his home to live in, and left me alone. Beyond that, he continued to remain a fatherly uncle to me through the vicissitudes of time.

He suddenly passed away on 16 March, 2008, after only a week’s hospitalization for pneumonia and back problems. But these problems were swept over by septicemia, the powerful infection contracted in hospitals (which is found in India in high frequency), which rapidly gained control over his various organs and proved fatal. Some people believe that the fatal blow came from the festering tuberculosis that had invaded his lower vertebrae much earlier than his final hospital visit. For a man who had never spent a night in a hospital, and who possessed superior health genes and who maintained it with a tenacious and obsessive discipline, the manner of his demise was painfully surprising. People took cold comfort in the fact that it was the hospital infection, septicemia, that killed him and not his health.

With Papaji’s departure, Kauls lost the last pillar of their clan. His iron strength of character, his keenness of mind, his robust will to live, and his durable wisdom made him into an iconic figure. Kauls who knew him well will keep on thinking about this larger-than-life person till their end. If an epithetical pronouncement were made about his understanding of human life, it would be the following words from Shakespear’s play Macbeth, which he cherished passionately:

“Out, out, brief candle! Life’s is but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

2. The Spark and The Spine – Papa Ji’s Eulogy

This is the eulogy I wrote immediately after Papaji’s passing away.

Papaji – Dwarika Nath Kaul (1920-2008)

How shall one remember a father, an uncle, and a friend who was at once a man of high principles, intellectually sharp, very human, and simple? How had all these qualities coalesced in one man always mystified the people who knew him? His personality shined in every important phase of his life. His laughter was invigorating and infectious and he loved to be among his family and friends. He took the hard and rough of life with equanimity and discipline.

Papaji was born in a large family in Srinagar in 1920. His father, Pt. Sudharshan Kaul, became to be the senior most non-English police officer in Jammu And Kashmir state. Papaji was a shy and an introverted boy who minded his books diligently. In fact, he was found to be a very brainy child, who went on to do brilliantly at his studies. After high achievements at State High School and Sri Partap College he went on to attend Government College, Lahore, which was considered to be the Oxford University of India those days. He graduated M.A. in English with distinction from it. Due to the untimely death of his father, at the age of fifty-four, he returned to Kashmir and plunged into taking care of his family. After a short stint as a lecturer in English in Sri Partap College, he qualified in the Kashmir Civil Service and joined the state police force. He steadily progressed through the ranks, ending his career as the Inspector General of Police of the state. He distinguished himself by his brilliance, discipline, and character. Being highly principled he was much feared at his work, both by his subordinates as well as by his superiors, though for different reasons. Being among the few non-bribe taking officers in the state made his superiors uncomfortable with him, and his intellectual stature and high-mindedness made them nervous. It took a lot of character and tenacity those days to maintain one’s principles.

He called his job as a “thief catcher”, which he said he did to make a living. For nurturing his soul he immersed himself in the world of literature and philosophy. He read widely and eclectically. He wrote many articles during and after his police career on important subjects, some of which were published in his book “Reflections on Police, Society, And Allied Subjects.” He was an aficionado of both English and Urdu literatures. He could quote with equal fluency and panache a Shakespeare or a Ghalib. Sometimes one wondered whether his intellect was wasted in police, when he could have contributed at a higher level in an academic or a national level planning job. He would have made a fine ambassador for India to a foreign country or been utilized for other high intellectual type of positions. But our Central Government often does know who its stars are. Alas, a high-level resource was left unused.

He lost his wife, Pyari, in 1976, when she was only fifty-two. This inflicted a deep wound in his life which he was never able to heal. But his perseverance and discipline prevailed and he spent the rest of his life absorbed in books and meeting his relatives and friends. He had wanted to continue living in Kashmir after his retirement in his house called “Simriti,” named by him in memory of his earlier life, but the war in Kashmir forced him to move to New Delhi. This adjustment was necessarily laced with trauma.

In the family life with him we enjoyed his sharp wit, humor, moral support, and practical advice. He was peripatetic, often walking many kilometers to see his relatives and friends, which also satisfied his life-long need for physical exercise. His tastes were fine and sparse. Overdoing was not his style. He endeavored to be a wholly independent man, which given the nature of life, was not easy. He many times let the ugly aspects of life get the better of him, turning him into a pessimist. But he was a staunch realist and believed in a pragmatic approach to solve life’s problems.

Today we mourn him but tomorrow we will miss him. We will miss his strength of character, his trustworthiness, his wise counsel, and the sharpness of his mind. He was one of the beacons of light in our family and that light will endure for many years to come. The legacy he leaves behind is our treasure.

Maharaj Kaul

Sufffern, New York

3.22.08

3. Life After Papaji

This is an essay written by me on Papaji in 2014.

He was an icon as well as an iconoclast, a traditionalist as well as a debunker of the traditions.

It has been six years since Papaji died but his persona as well his image has deeply descended in the Kaul clan mythology, despite his sharp and pungent treatment of some of its members and others at times. What has unconsciously and consciously impressed people has been his uncompromisable honesty and his unassailable character.

His absence from the clan is invisibly mourned. His intelligence, his sarcasm, his upbraiding of people, and his high-pitched voice are missed. He appeared to be the tower of strength.

He came from modest economic circumstances but by the dint of his intelligence and consistency he created a niche for himself in the society. He was an intellectual, but initiated more by intuition than by scholarship.

He took a police officer’s job rather than an English professor’s job because the former paid more and was more secure. Why he took a master’s degree in English is puzzling because he was not an artistic person. He should have studied physics, economics, or political science instead. This is among the many contradictions in his life. Basically, he had no vision of his life: he went along whatever was the current social style.

Papaji did not have much fun in life because of his deep conservatism and parsimoniousness. On philosophical level he wondered whether joy was possible in human life. In the earlier period of his life he was often glum and sedate. He believed life was set up by gods to punish man for some unknown sins. But later with considerable effort he incorporated some modicum of joy in his life. His brother, Babuji, called him a Devdas but without a Paroo. His personality can be echoed by the following two stanzas from Shakespeare’s plays King Lear and Macbeth:

“As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods,

They kill us for their sport.”

“Life’s is but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.”

Papaji’s honesty in the public life was so strong that we can use the American president Harry Truman’s aphorism, “The buck stops here.” He had forbidden police officers subordinate to him to enter his home because they tended to please his home people by bringing in gifts like fruits, bread, and other things. He once told me that if his son was implicated in some wrong-doing he would not hesitate to punish him. Such high character was a rarity in the Kashmir of those times.

Life was unfair to him as he deserved a much higher level of job than the best he had, like an ambassador’s job. He deserved a wife who had more acumen of intellect than she had. He complained a lot about life, still he went on living.

Today we have no leader in the Kaul clan. It is among other things a loose spectrum of many young people who are unaware of Kaul clan’s glory days and grand personalities. Which portends a gradual dissolution of the clan as we knew it. But everything in life finally fades in the mists of time.

Life after Papaji in the clan has been a lukewarm experience, adrift in uncertainty, like a rehearsal of life, instead of the life itself.

With all his flaws Papaji was a bulwark of moral strength. He stood by his principles most of the time. But his tepid personality often muted the vibrant colors of relationships, celebrations, and the carefree moments of the enjoyment of life.

I had a special relationship with Papaji. I often differed with him on philosophical matters. We exchanged about a hundred letters. One day I wish to publish them as they are about serious philosophical subjects. Papaji’s daughter Veena told me that after his death they found out that the only letters he had saved were those written by me.

Suffern, New York. March 29, 2014; Rev: Sept. 8,2017; Rev: September 9,2020

maharaj.kaul@yahoo.com

www.kaulscorner.com

Information on pics:

- Karan Singh giving an award to Papaji

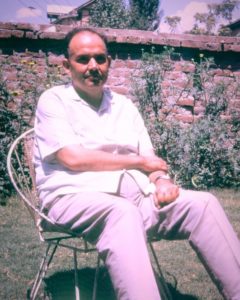

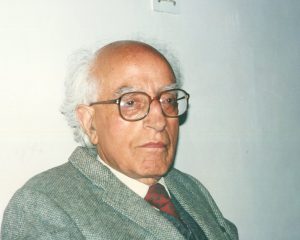

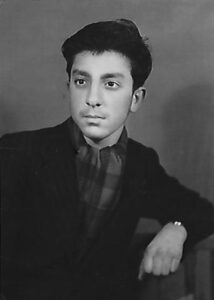

- Papaji

- Papaji

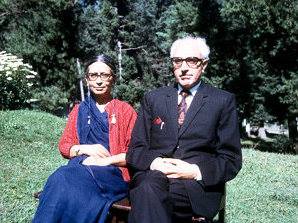

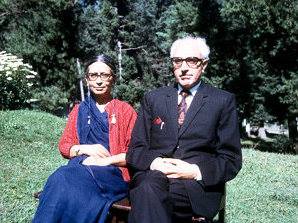

- Pyar & Papaji – pic taken by me in 1974 in Pahalgam

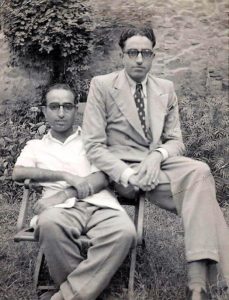

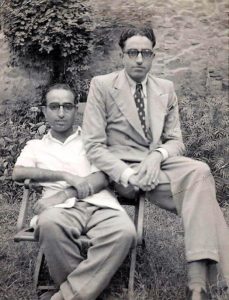

- Babuji & Papaji

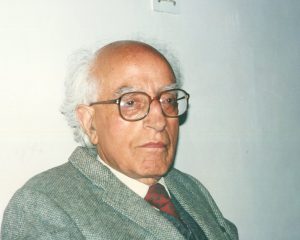

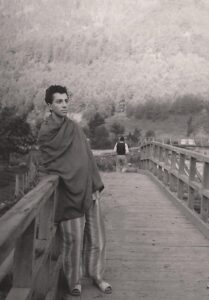

- Papaji – pic taken by me in 1980’s in Mandakani, New Delhi. Papaji liked it.

C.

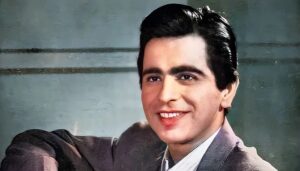

Dilip Kumar Is No More: It is a deep personal loss to me that Dilip Saab, one of the heroes of my life, passed away a few hours ago.I discovered him in my mid-teens when I was living in Srinagar, Kashmir. During those years there was not much going on in a teenager’s life except reading books, listening to music on Radio Kashmir, seeing movies, and imagining romances with pretty girls. The last item was more in the realm of imagination than in reality, as the existing morality strongly looked down upon it . When I saw the first Dilip Kumar movie, I was hypnotized. His emoting, speaking, walking, and everything else was sharp, sensitive, coming deep from his heart. And the tragedy roles he played were in sync with my soul. After seeing a Dilip Kumar movie I used be so moved, that for several days I would be knocked out. It would take me effort to come back to real life. After seeing his many movies I came to think that he must be a special personalty in his real life. My thinking came to be true after I delved deeply in his real life. I found that he was an intelligent and a sensitive man, who had a strong character. Also, I came to know that that he was very selective in the roles he played, was very good to people, so much so you could not criticize any person in Bollywood and beyond in his presence. If you did, he would come out with many good qualities and deeds that the criticized person had to his credit. In the last few years I had a wish that he live up to 100, to add aura to his personality. His life, beyond the cinema, I studied keenly. I found that he knew how to live it, true to his personality. He maintained his artistic personality, knitting it with realism, and constrained to practical difficulties of life. The same qualities of sensitivity, intelligence, and character he used in his movie roles, he also applied to his life. He was selective in his roles, so that he ended up working in less than 60 films; while actors of his level of success would act in more than 100. This was a delineation of his character. He did not want to work in all kind of cheap movies, just to make money.Using Tagore’s language, Dilip Kumar was greater than his deeds and truer than his surroundings. His name will not only live on in Bollywood, but in India, and beyond. He was the first hero of my life; subsequently, I added four other heroes, as I grew up. But none of them chipped away anything from the magic of Dilip Saab. Today my hero has left me, but his life will keep on inspiring me by its sensitivity, tenacity, talent, realism, and strong character. Maharaj Kaul

Dilip Kumar Is No More: It is a deep personal loss to me that Dilip Saab, one of the heroes of my life, passed away a few hours ago.I discovered him in my mid-teens when I was living in Srinagar, Kashmir. During those years there was not much going on in a teenager’s life except reading books, listening to music on Radio Kashmir, seeing movies, and imagining romances with pretty girls. The last item was more in the realm of imagination than in reality, as the existing morality strongly looked down upon it . When I saw the first Dilip Kumar movie, I was hypnotized. His emoting, speaking, walking, and everything else was sharp, sensitive, coming deep from his heart. And the tragedy roles he played were in sync with my soul. After seeing a Dilip Kumar movie I used be so moved, that for several days I would be knocked out. It would take me effort to come back to real life. After seeing his many movies I came to think that he must be a special personalty in his real life. My thinking came to be true after I delved deeply in his real life. I found that he was an intelligent and a sensitive man, who had a strong character. Also, I came to know that that he was very selective in the roles he played, was very good to people, so much so you could not criticize any person in Bollywood and beyond in his presence. If you did, he would come out with many good qualities and deeds that the criticized person had to his credit. In the last few years I had a wish that he live up to 100, to add aura to his personality. His life, beyond the cinema, I studied keenly. I found that he knew how to live it, true to his personality. He maintained his artistic personality, knitting it with realism, and constrained to practical difficulties of life. The same qualities of sensitivity, intelligence, and character he used in his movie roles, he also applied to his life. He was selective in his roles, so that he ended up working in less than 60 films; while actors of his level of success would act in more than 100. This was a delineation of his character. He did not want to work in all kind of cheap movies, just to make money.Using Tagore’s language, Dilip Kumar was greater than his deeds and truer than his surroundings. His name will not only live on in Bollywood, but in India, and beyond. He was the first hero of my life; subsequently, I added four other heroes, as I grew up. But none of them chipped away anything from the magic of Dilip Saab. Today my hero has left me, but his life will keep on inspiring me by its sensitivity, tenacity, talent, realism, and strong character. Maharaj Kaul