Reminiscences of Bhabi – Kamla Cherwoo

It seems some things in life are destined to fail, especially among those that you cherish the most. When I was a boy, I used to think I would marry a village belle. It was because I thought she would be pure of heart and simple in demeanor compared to a city slicker. Good luck opened up for me, I married one. Along with that came the relationship with a village family, which I was attracted to for the same reason as the belle.

It was in late February 1969 when I first met Bhabi, Kamala Cherwoo. The meeting was initiated by her, as she wanted to see me, the first time, and talk with me before I was married with her daughter, Mohini, which was scheduled about a week later, on March 2, 1969.

I did not have any inkling of what kind of a person and a personality she was, but I had never heard anything bad about the Cherwoo family, in the Kashmiri Pandit society in Kashmir those days. She had set the meeting in a restaurant in the main bazaar of Jammu, escorted by her middle son.

Setting my eyes on her the first time, I found a very compassionate person, who held herself in good control, and was diligent in being respectful and charming to the person she was meeting. I was buoyed by her kindness, transparency, and generous respect she gave me. Years down the road this initial assessment of her has never wavered.

Bhabi was born in Srinagar, Kashmir, in a Kashmiri Pandit family. Her father Srikanth Mattoo was a medical doctor, specializing in pathology. She had a younger sister, who died young. Lack of a male offspring compelled her parents to adopt a son, Jawahar Lal, considerably younger than her.

At the age of fifteen or sixteen Bhabi was married in Cherwoo family, living in Anantnag, about thirty-five miles south of Srinagar. Her husband, Vish Nath, was the younger son of the family patriarch, Halder Joo Cherwoo. The family was engaged in the wholesale business in edibles, spices, and cloth. Their success in it had made them into a well to do family, concomitantly earning them social status. Cherwoos were a well-knit clan, spread over a few families, living at the same general place. The families were independent and yet had the thread of togetherness connecting them.

How a sixteen-year-old girl learned to live with them is the quintessence of Bhabi. By her culture and by her personality, Bhabi did not fit with Cherwoos, but yet she successfully lived with them virtually all her life; in fact, becoming one of their leaders. She molded herself to the new reality, using her salient qualities of tolerance, patience, inter-personal skills, and diplomacy, to be in control of the family; which her status as the family scion’s wife demanded. She acquired the ability of deflating the family feuds and giving it the semblance of unity and congruity.

Even bigger challenge for Bhabi was to live with her husband, Babuji. He was of fragile tolerance, hyper sensitive about his self-image, dictatorial, and temperamental. Here was a colossal challenge for Bhabi. She had no special training to meet it, except to the extent what almost all Indian women of her generation had when they got married. Deep respect and tolerance for their in-laws and the husbands, a religious zeal to succeed in this endeavor, and, above all, not mind the hurt if bruised in interactions with them. It was a missionary work they had silently agreed to do. Over the years Bhabi managed to live with Babuji by sacrificing her right of equality, perseverance, and tactfulness. Over time their marriage became one of gratitude, tolerance, and love.

After my marriage in Cherwoo family, I visited them several times during my visits to India from U.S. Also, they reciprocated visiting me and my wife in U.S. several times. Because of these I came to know Bhabi more.

During her almost annual visits to U.S., after the demise of Babuji in 1995, at the age of seventy-three, up to early 2,000’s, she stayed with us without fail, along with staying with her two sons. She was disciplined in daily activities: walking, eating, sleeping, and praying. She was always in control of her mind. But it is not difficult to imagine that at times she would have been travelling down her memory lane to the great times of Cherwoo’s in Anantnag, her times with Babuji, and other relatives. The mega-family atmosphere has its own charms. Then, especially living in Kashmir, her birthplace, had its own gravitational pull of memories of childhood and youth, when her children were born and raised. It is a stroke of misfortune when a person is compelled to move from his place of birth, childhood, and youth to another country. Babuji’s untimely demise, I am certain, has played a significant part in her subsequent emotional life. She would not engage me with her past, and, I guess, anyone else. That came from her inherent shyness and control over herself. For the same reasons she would not complain about anything to me.

I several times went to the airport to receive her when she was coming from India. During travelling she would put on an aggressive posture, just to feel secure and be alert. After my retirement I would generally be the one attending to her lunch and dinner. I, also, made sure that we had honey in the house, which along with milk, she would take before going to bed. She would occasionally take walks outside the house. She had a long praying period in the morning. Whenever her middle son Balji would visit us she would be excited, as he was her favorite child. He had equally a weakness for her.

Overall, Babi’s personality is unique. She is a long suffering and a controlled personality, who believes in the grace of God, and is at peace with the world. No wonder all this has contributed to her longevity.

We developed a special relationship, which continued on till 2013, after which due to my divorce with my wife, it abruptly ended. It was not her who ended it, but her children, who decided not to tell her about the divorce, on the assumption that doing so would jeopardize her health, as she was already in her 90’s. Nothing could have been farther from the reality. Bhabi had seen many deaths among her close relatives in her lifetime, including that of her beloved Babuji; my and Mohini’s divorce would not have been unbearable for her. This was a tragic situation for me, as I could not do anything to mitigate it.

I treasure her gentle touch, cool control, and sheer goodness. My memory flashes to trips we took to Pahalgam, Khirbhawani, and the times we spent in New York. She was a shaft of tranquility, forbearance, and silent fortitude; the kind of which I have only seen in my mother and a few others.

But memories of her will remain strong in my universe, as there was a relationship of love and respect between us. I have been told that old age has encumbered her heavily. I am certain that she will bear it gracefully, as she has borne other calamities in her life.

I am ending this tribute with the following words:

Upon the altar of life there are not enough sacrifices one can make,Bhabi burnt her ego and interests to irradiate her world with compassion and love.

Notes:

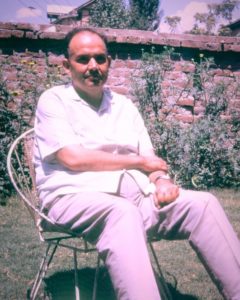

- All pictures taken by me.

- The frontispiece picture of Bhabi taken in Sept., 2007.

- The pictures below are of Bhabi, Babuji, and Kakni (Bhabi’s mother)

Suffern, New York, May 25; Rev: May 26, 2020

maharaj.kaul@yahoo.com