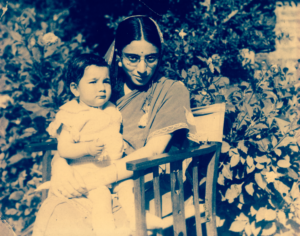

I am said to have been born around five in the morning (not a convenient time for deliveries even in modern times) in a hospital, from where my mother and I were taken to my maternal grandfather’s house, which contained a sprawling household of six brothers, their families, and a battalion of servants. I have always wanted to meet the doctor who helped my birth for some vague emotional reasons, but have not been able to do so. I guess my arrival triggered some joy and excitement in that household, as my mother was her father’s favorite child and was a person well-liked by people due to her modesty, sensitivity, and beauty. I have been told that I was generally a tranquil baby, not given to too many sessions of weeping and bad moods. Added to these were my buxomness and good looks, making me an irresistibly cuddly baby to hug and hold in one’s lap. As I grew up, my arms and hands became plump, attracting some people to them as they appeared soft playthings. At about the age of two, I comfortably sat in the lap of my newly-married aunt (father’s younger brother Papaji’s wife), who was still a bride, thinking her to be my mother, as she wore glasses as my mother did. I do not have any recollection of my father from this period of my life, which may be due to a Kashmiri father’s reluctance to handle a baby in those times, which would detract from his culturally required macho image. Although somewhat lessened with time, this inhibition to show love by a Kashmiri father to his offspring, stayed on throughout his life. No wonder almost all fathers looked stern to their children those times even after they became adults. This cultural deficit curtailed many familial relationships from their full bloom.

The first memory of my father that I have is when I was about three or four years old. He held me in a half-sleepy state in his arms and carried me from the family room to the bedroom, where he put me in bed. Besides the cultural inhibition of demonstrating love to one’s child, there was another reason reinforcing this behavior. In a joint family, where parents, uncles, aunts, and their children, and grown-up sons, their wives, and their children lived together, one of the commandments of peaceful coexistence was not to display any more love to your child than you would display to other children in the family. No wonder many children reared up in the old Pandit families grew up to be diffident, socially inept, and generally confused. Kashmiris were very primitive in raising their children because of their preconceived notion that essentially children grew naturally by themselves.

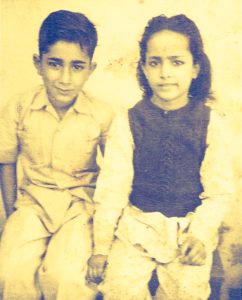

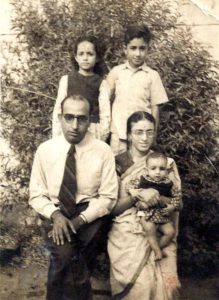

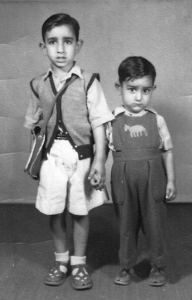

Two years after my birth, my sister Lalita was born. She somehow made my father throw off some of his social reserve and show his love for her. At least I felt that my father was not that stern after all. Lalita mixed with people more readily than me. This quality stayed with her through her adult life and she became a very social person and highly popular. The two of us provided two contrasting personalities—one shy, reluctant to come out of his skin, and broodingly contemplating the scene in front of him; the other eager to participate in whatever event was taking place, very inclined to please people, and altogether practical minded. Unconsciously, I began bonding with her. As she was my only sister, and at that time my only sibling, my love for her grew strong. We were separated for several years when in 1953 she and my mother returned to New Delhi to join my father when he found a new job, after having lost the earlier one. My father thought that it was better for my education to stay on in Kashmir. After that, in the late 50s, my father was posted abroad and the connection between Lalita and me remained in limbo for many years till we revived it in 1962 when I came to USA. After this we continued to enjoy a close relationship.

It is one of the supreme ironies of life that one does not get to select one’s name. First a human being is brought to this world without being asked whether he would like to come here and then he is given a name, followed by the attachment of many other things to him, like culture, upbringing, education, etc., some of which the newcomer may have to fight to get rid of or modify for the most of his life. I was given the name Maharaj Krishen by my paternal grandmother, Kakni, perhaps in tune with the name Avtar Krishen she had given to her son. My name is the name of a popular Hindu God, Krishna. The first name Maharaj means king, which in my name is used as a title of Krishna. So, I am King Krishna! Certainly, I have not lived up to his religious beliefs and work, nor have I been as romantic as he is mythologized to have been. Living with such an awe-inspiring name became burdensome pretty soon and I had no choice but to ignore it and use it only mechanically, bereft of its solemnity and message. Later on, while living in the US, my colleagues at work abridged my first name to Raj. For the sake of the style of brevity of modern times, I had already dropped my middle name Krishen. As per Kashmiri Pandit customs, I was also given a name by my matamal (mother’s maiden family). It was Bansi Lal, which is another name for Lord Krishna. They also gave me a pet name, Baby. I was told that it came from an Englishwoman who visited my maternal grandfather’s family and called me so after seeing me. I had a lot of difficulty in coping with this name, as my friends teased me on still being a baby, even after I had left that age a long time back. It was only after my tenth year that the traces of that name disappeared, the causes of which I still do not know.

At the time of my birth, our family had, apart from my grandfather and grandmother, their one married son, two unmarried sons, two unmarried daughters, a caretaker, and perhaps one or two relatives, who were in difficult circumstances and were living with us at the benevolence of my grandfather. My grandfather was the senior-most Kashmiri in the state police department. All officers above him were Englishmen. He was tall and fair, mild-mannered, and given to a low profile due to his shyness and humility. He was fair and compassionate. Our meetings took place when I was only a few months old, as he passed away shortly after my birth, at the age of 54. Many people, both within and out of our family, attributed my grandfather’s death to a bad omen I brought to him with my birth. I did not have any recollection of him, having seen him when I was too young to hold any memories. Because of this, my recurring childhood dream, in which I would go to his room to see him, often snapped abruptly. From what was told to me by our family members, my grandfather and other members of the household spent a few traumatic hours just before his death.

The story runs that his physician, a renowned Kashmiri physician, Dr Gaush Lal Kaul, while treating him for some illness had allowed him to eat heavily-spiced meat only at my grandfather’s strong request. However, he forbade him from drinking water with the meal or even after that. I am highly skeptical that such a treatment would be used in modern medicine. Anyway, my grandfather had his dinner which included rogan josh and gadda nadir—both Kashmiri delicacies and highly spiced. It is quite rare that during or after partaking a highly-spiced Kashmiri meal one would not take some water to dilute the effect of the spices. My grandfather, I am sure, after exercising some self-control, could not help but ask for water to relieve him of the discomfort caused by the heavy dose of spices which included chili powder in generous amounts. People around him braced themselves and continued to refuse to comply with his request. Though they understood his discomfort and did not appreciate the idea of refusing his demand, they restrained themselves only to help his illness. As the ordeal continued, my grandfather’s wails for water were loud enough to awaken the entire Kaul Compound, in which many of our relatives were sleeping peacefully. Though they all knew that the grandfather could not be given water, its denial to an ill and very thirsty man, pierced their hearts. My grandfather passed away soon after this event.

My grandfather’s untimely death at the age of 54 shook his household, where he was the only wage earner. Having been a government employee, though at a good level, running a joint family and dying at an early age, it was not surprising that he did not leave much money behind. Under these extreme conditions, wrapped with urgency, my father quickly accepted the first job he was able to get. He became a court sub- inspector, a position within the police department, which required legal expertise, which was met with his MALLB education. It was not a true police officer’s position. Incidentally, he did not have the physical wherewithal to look a police officer, although he certainly could have done the job. But it was not a job of his choice in its content, status and remuneration. My oldest uncle Papaji also acted as another pair of shoulders supporting the family’s economic and social burdens at this time of crisis.

Our family was economically middle class, socially respectable, and quite modern in outlook and style compared to the common Kashmiri Pandit family. The fact that we were not traditional Kashmiri Pandits was held against us by our peers. Although my grandfather was somewhat receptive to some notions of modernity, he was steeped enough in the Pandit tradition to be able to extricate himself from it. It was left to my father and my elder uncle to cross the line to modernity. The brothers shared a parallel outlook toward most of the things, as the age difference between them was only three years. Our family unconsciously carried a sense of superiority over most of the others but they made sure that their propitious decency was never diminished in the social intercourse. The charges of arrogance levied by others on us were right only to the extent of its existence on a superficial level. Beneath the social skin Kauls meant well but sometimes came across as insensitive and indifferent due to the lack of proper inhibitions and fine tuning of public relations. Like other Kashmiris, my family attached high value to wealth, job position, and smartness. The veneer of intellectuality on my family was brushed in by my father and elder uncle. Both were highly intelligent, well read, forward-looking and highly opinionated. They fervently attacked corruption and social, cultural, and religious hypocrisies. Many of the family’s pre-dinner and post-dinner conversations revolved around these topics and other recent events.

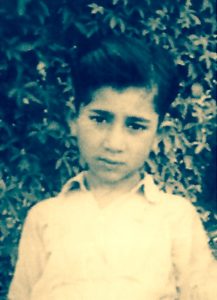

By the time I was four or five, and still not sent to school, the teacher who was already coaching my younger uncle (four years elder to me) was asked to teach me also. The day the teacher was supposed to give me the first lesson I was smitten with fear, resulting in my prolonged crying. Grown-ups around me were at a loss to understand what bothered me so much to make my cry so intensely and for so long. True to my nature, I did not share with my caretakers and sympathizers what roiled me. What I now think happened to me then was that I perceived that I was going into a long slavery. This fear stemmed from the fact that in those times a teacher could yell and spank, or use other methods to correct a pupil’s behavior to make him suitable to receive education. However, after the first class, I was not as petrified as before. This arrangement with the teacher lasted for a few years till I was eight years old. I had already started feeling a bit lonely. The joint family was not a good place for a sensitive boy like me to live in. I needed attention of my parents but that was stifled by the joint family environment. There was a chink of solace in my life when I used to spend time in my maternal grandfather’s home. Here was a family which had lesser inhibitions in displaying warmth and caring than my family was comfortable with, in spite of it also being a joint family. Furthermore, by virtue of my mother being the favorite child of her father, my maternal grandfather’s love was automatically transferred to me. He completely doted on me. But the irony was that the visits to my maternal grandfather’s home did not exceed more than seven to eight a year. My father was very serious about not letting my education getting pinched by my absence from home.

One day, my maternal grandfather, Baaji (Karihaloo), came to our home to meet us. After spending an hour or two, he started to leave. As he got up, he grabbed my hand and said that he was going to take me to his home for a few days. On hearing this idea from Baaji, my father at once sternly objected to it. Baaji was taken aback by this reaction and demanded to know the reason behind it. My father cited the harmful effect it would have on my education. Baaji pleaded that at my education level, an absence for a few days would not amount to any significant loss. At this point, as if by reflex, Baaji grabbed my left arm and started to drag me toward the door. But my father, already one step ahead in getting fired up by the situation, responded by grabbing my right arm and pulling me toward him. I was scared by this imbroglio between the two strong personalities, one driven by emotion and other by principle. I was especially scared of my father’s aroused temper, of which I already had a few but strong experiences. I wanted to go with Baiji but was afraid to tell that to my father. For several minutes, which seemed like eternity to me, the two grown-up men continued to pull me in opposite directions, as if I was the rope in a tug-of-war, all the while arguing intensely about the merits of my missing tuitions for a few days.

Baaji was an over-stout man with a large-diameter waist. He used to wear a long buttoned-down jacket called achkan (a long Nehru style jacket), accompanied by a turban and walking cane. The image of him juxtaposed with a younger man and a child in a physical tussle was at once awkward, as well as comic. Finally, my father prevailed, not in the least due to the fact that Baiji was deferential to him, as a father-in-law would be to his son-in-law in the Indian milieu. The duel ended, sending Baaji dejectedly toward the house exit alone and I broke free from the tussle and went to my room to restore my tousled emotions. Later in my life, this insignificant event became a haunting image of my adult life. I used it as a living image of conflict, when two ideas playing on me were antipodal. On one hand, I was idealistic and sensitive, while on the other, I was compelled to respect reality and the ways of the world. I cared for people but was repelled by some who considered themselves even more significant than the nature that gives us life.

By the age of eight, I was trusted enough by the grown-ups and they confided in me the problems they faced with other members of the Kaul clan. Many times, both the conflicting members and groups would unburden their problems with each other to me. They felt that I was a good, comforting kid, whose sympathy toward them would relieve them of some discomfort they had incurred in an inter-member or inter-group imbroglio. This experience on an impressionable boy like me induced me to think on human relationships and beyond that to the nature of human life itself—an odyssey that I am still not through with. While I was generally liked by people, I felt close only to a few. This attitude, I believe, was triggered by my apprehension of being hurt in a close relationship. While I had a tremendous need to be loved, but my propensity to love was inhibited.

Our family was a big star in the Kaul clan galaxy, whose members lived adjacently or contiguously in a cluster of about nine families in six houses, forming the hub I call Kaul Compound, at Malikyar, Srinagar—the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir. The families were united by many common personality attributes beside the last name. As a clan they exhibited self-confidence, pride, self-consciousness, outspokenness, and a more moderate religious intensity than an average Kashmiri Pandit’s. The social atmosphere within the Kaul clan was generally warm and friendly. Members were willing to help each other. For the outside world they kept up the image of clan unity and were genuinely proud of it. The clan was also renowned for its sense of humor. Reciting real or made-up comic stories about its members and outsiders was a very popular way to have fun. We had a renowned in-house comic, Budhkak, whose talents in the field were of professional level. The atmosphere of hilariousness and light-mindedness was not very common among Kashmiri Pandits, as they were generally of serious disposition and were socially stiff. In fact, there was an ambition among many Kauls to be the top joke makers. That is why many of the married Kaul girls would often feel compelled to return to their original homes, as soon as it was appropriate, to partake of its delectable joviality. But the joke-making sometimes landed many Kauls into trouble with the outside world, as many people felt they were insulted or were looked down upon. At times, the jokes backfired in sensitive in-law relationships. But because the clan members believed that the jokes were made with a good heart, solely to amuse others and themselves, they did not take the adverse reactions seriously.

The cockiness combined with the backfired jokes lent the Kauls an image of arrogance. Much as they tried over years to shed off this image, it has not shown any tangible diminution. The image has more or less endured, even with the clan diffusion over the world. Also, their moderate religious intensity and superficial adherence to some social mores created an image of their not belonging to the mainstream Kashmiri Pandit culture. That image was prized by my father and uncle, who zealously led the family in that direction. The influence of the brothers was consciously or unconsciously felt by the entire clan. Their faith in modernism over many aspects of traditional Kashmiri Pandit culture was strong and totally unpretentious. Be it as good as it may, in their overzealousness to follow the modern Western thinking in many aspects of life, they colored their perceptions of the many stellar items of the old Kashmiri Pandit culture and softened their umbilical connections with their roots. Over time, my uncle became a matured and renowned debunker of Kashmir Pandit culture and ethos.

Being well-liked by people generally was a good antidote for my evolving loneliness. I seemed like a lost soul bereft of any anchor in sight. Though many people liked me, they thought me morose and melancholic. Women seemed to like me more than men did, in parallel with my similar inclination toward them. I found them more caring and I felt that I was gaining more confidence in responding to their kind of emotions as time went by. My father was the person I feared the most. It came first from the cultural influence of the day when fathers had to be serious and stern so as to shroud themselves with an aura of authority, which satisfied their egos and also helped them in guiding their offspring’s lives. Furthermore, my father was shy and inept to handle children. My mother showered more care on me, but being scared of the joint family environment, she was inhibited to go all the way. So, I grew up like a large number of other kids in the community—a faceless and diffident personality. It was only much later in my life that I was able to jettison this baggage. My shyness hung on me even through college years. Only with the birth of my sister, two years after mine, did my father begin to slowly lose his shyness and inhibitions, and express love to his children publicly.

Our family left Kashmir in late 1948. The air trip to New Delhi was historic, as it was momentous for our family. It was historic because air travel in India was still in its infancy and an air trip from Srinagar to New Delhi was usually taken only by the high government officials and businessmen to accomplish some time-sensitive and important work. Also, it was quite expensive. Since my father had been living alone for about a year in New Delhi, he wanted his family to join him immediately. So, he did not want to take any chances with road blockages and breaches due to the icy winter we were in. But ironically the air journey we settled on was delayed by several weeks due to extreme weather conditions which are quite common in Kashmir during winter.

I remember the glitter of Safdarjung Airport at New Delhi hitting me right on when we landed there. Everything looked big and shining compared to the Srinagar Airport. My father’s fatigue due to the long wait that day at the airport seemed to disappear on seeing us. We were his answered prayers, the sweet companions in his future journey in life. New Delhi was a sprawling metropolis of a newly-independent nation. It seemed to be brimming with the excitement of setting up an indigenous government after some 1000 years of foreign rule and awash with pride for their country, for what it has been and what it could be. We seemed to have left our grey existences behind us and felt braced for a new beginning, spawning a new iridescent hope for a better life.

When I went to school for the first time, it was a totally new experience for me. It was a private school called Bal Bharti School, located in Ajmal Khan area. Based on the level of my home tutoring in Kashmir, I was placed in the fifth grade. I adjusted to the school rapidly and seemed to have no problems at all. Because of the good extra-curricular programs in the school, my shyness had a good chance of wearing off. Academically, I did well. I was promoted from the fifth grade to the seventh grade, without having to sit in the sixth grade. I was particularly strong in Mathematics and English. One day, in the seventh-grade English class, the teacher drilled us through some difficult word spellings. One of the words was ‘dysentery’. When the teacher went over the word listing the second time to see how much we had retained, I was the only one who remembered the spelling of that word. All eyes in the classroom were locked on my face. The teacher repeated the list a few more times, aiming at a hundred per cent retention. Every time I would be the only student remembering the spelling of dysentery. Now, I became very conscious of it because of what the word meant. The next time when the teacher asked the spelling of that word again from our class, I chose to keep quiet. The teacher and all the students looked at me aghast, failing to understand how could I suddenly forget the spelling of the word that seemed to have sunk deep into my brain. But I stoically maintained that I had forgotten its spelling.

The first stirrings of my romantic life erupted when I was in the seventh grade. There was a bouncy, charming, tall Sikh girl in my class. Her smooth demeanor and magnetic smile were irresistible to me. She liked me and was inclined to be my friend but it was clear that I had to take the traditional ‘male initiative’ to usher in the romantic friendship between us. Our romance remained a hedge romance (a popular Indian English phrase in vogue at that time describing the typical romantic relationship between college-age boys and girls, where physical intimacy was a taboo). The apex of our romance would occur at the school quitting time, when we walked together. But my romance with her died a natural death when I returned to Srinagar in 1952. The possibility of what might have blossomed between us remains an uncharted dream. The most ironic aspect of this relationship was that the girl in question was called Mohini, the same name that the lady I married many years later had. That marriage lasted for forty-five years, tragically ending in 2014.

Two significant things happened in the Delhi phase of my life. On 2 June 1949, my mother gave birth to my brother Babu at Tis Hazari Hospital. He caught the attention of our father at an emotional level which the latter had never displayed toward his two elder children. This was good for my father’s morale as he finally had something to identify with, something to look forward to. Two years later, on 27 August 1951, my youngest brother Kaka was born. The two of them could not have been more different. Their personalities chased each other like a day chases night but never getting together. Babu was aggressive, ambitious, socially active, and extroverted; Kaka was shy, mild, ambitious, socially aloof, and introverted. Babu knew what he wanted in life and focused on it early on. He did not have much aptitude for very hard work and did not go very deep in issues. Like our father, he embraced practical knowledge and left the subjects of philosophy, psychology, and science to others. Kaka was hard working and kept his feelings to himself. No one knew what hurt him, what excited him, or even what he was up to. He was a walking secret. But his innate goodness was writ large on his face and people liked him instantly. Indian culture favored his personality over Babu’s, but my father lionized Babu because he possessed aggressiveness, which my father had come to believe was a necessary ingredient for successful living, and which he himself had to make an effort to have at times. Arrival of the new members in the family altered a significant thing in it. Lalita and I used to call our father and mother Babuji and Bhabi and now they became Daddy and Mummy. I did not like the change but had no choice but to follow it.

(These boyhood reminiscences will be followed by Reminiscences of Adolescence in Kashmir)

Note: the above essay has been adapted from my book Inclinations and Reality.

Suffern, New York, March 8,2021

www.kaulscorner.com

maharaj.kaul@yahoo.com